11 urban myths about franking credits

By Kate Howitt of Fidelity International

The decision to introduce dividend imputation has provided an unforeseen benefit for Australia, perhaps one that is still not fully appreciated by policy makers – it has made Australian companies manage their capital more efficiently. That makes them sounder investments.

Yet this benefit appears to be in jeopardy because the debate about the value of dividend imputation is obscured by myths. This submission seeks to puncture these illusions in the hope that policy makers will possess the information they need when judging the effectiveness of a tax system that has served Australia well since 1987

Myth 1: Franking is an anachronism; Australia should modernise its tax structure

Reality: Franking’s primary benefits – avoiding double taxation, removing the incentive for high levels of corporate debt – remain valid

Dividend imputation was introduced to avoid the unfairness of taxing company profits twice. That motivation still stands. Without franking, the interest expense deduction would be expected to have more influence in corporate funding. Since the introduction of franking, Australian companies have increased their gearing levels – in line with the secular decline in interest rates in the western world – but to a lesser extent than US companies have.

Not creating further incentives for Australian corporates to take on more debt is highly desirable since negative gearing has created an incentive for high levels of borrowing by the household sector:

Myth 2: Franking is all about the tax refunds

Reality: Franking’s most important influence has been on capital allocation within the economy

Growth and innovation require that funds available for investment are channelled to the most promising opportunities. Franking facilitates this by automatically prompting companies that generate the most cash flow to pay it out, which allows shareholders to reinvest that cash flow into the best opportunities. Without franking, this capital-recycling process would be diminished due to the friction of corporate tax reducing the funds available to be reinvested.

This recycling is necessary in Australia, which is an economy of cash-flow “haves” and cash-flow “have nots”. As the charts below show, Australia has a greater proportion of its market comprised of larger companies. Further, smaller companies in the US tend to generate higher returns than their counterparts in Australia. This means that Australia’s smaller companies are more reliant on attracting the dividends flowing from the largest stocks.

Myth 3: Australia has enjoyed extended economic growth. Franking has played no part in this

Reality: It is likely that franking has contributed to Australia’s lower economic volatility

Franking constrains corporate reinvestment. If we assume that companies will fund their best projects first, their second-best projects second, etc., then constrained reinvestment should result in better outcomes. If only the best projects are funded, then those projects are likely to be more robust through the economic cycle. At the margin, this likely brings greater stability to employment, consumer sentiment, etc.

As expected, corporate returns in Australia have improved, and have advanced more than returns in the US:

This holds true even after excluding the anomalous mining and tech sectors:

What’s more, the quality of returns has improved, as the variance of returns has diminished and the persistence of high returns has increased:

Myth 4: If Australian companies have higher payout ratios, it must be at the expense of capex – but we need more investment now, not less

Reality: Relative to US companies, Australian companies pay higher dividends and also invest more; the key difference is that Australian companies run their balance sheets more efficiently

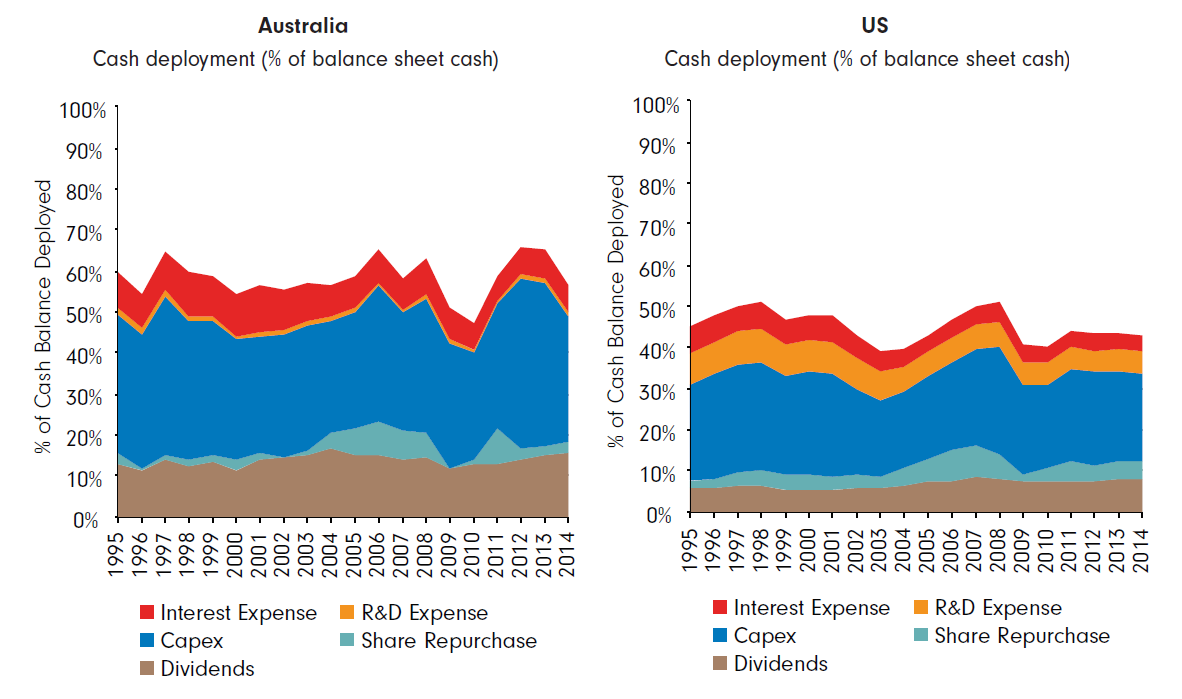

In this instance, it’s best to look at companies’ overall use of cash. Despite higher payouts (and higher interest expense), Australian companies do not spend less on capex. There is no evidence that higher payouts have led to lower levels of investment.

The significant difference between the two sets of companies is the “white space” – which is cash that is left undeployed. Australian companies run their balance sheets more efficiently than do US companies. This benefits the Australian economy

Myth 5: Franking promotes higher payouts, which reduces reinvestment and lowers future growth

Reality: Higher payouts indicate higher future earnings growth – there is no income-growth trade-off

Conventional wisdom holds that companies retain more earnings when growth opportunities are ample and fruitful. Therefore, the paying out of large amounts of dividends signals a paucity of good growth opportunities. However, academic analysis challenges this view. Arnott and Asness (2003) used 130 years’ worth of data to show that it is high-payout firms that generate the best earnings growth over time.

The work of Zhou and Ruland (2006) supported the Arnott and Asness conclusion. By using data over 50 years, their paper showed that high-dividend-payout companies tend to experience “strong, not weak, future earnings growth”.

Despite Australian companies increasing their payout ratios after the introduction of franking, asset growth rates have increased:

Myth 6: Franking turns the Australian market into a high-yield, low-price-return market

Reality: Higher dividend-paying share markets deliver higher price returns – even at the aggregate level. There is no income-growth trade-off

Conventional wisdom assumes that high-dividend stocks offer low growth potential. The perception is that companies that return much of their earnings to shareholders have less to invest than companies that retain their profits. But again this is not supported by the data: over time, high-yielding stock markets have offered the highest total shareholder returns.

Analysis by the London Business School shows that the highest-yielding stock markets returned 13.5% p.a. from 1900 to 2010 versus 5.5% p.a. from the lowest-yielding markets. As the chart below shows, the highest-yielding markets were the top performers over every consecutive quarter-century period last century and over the first decade of the 21st century

Australia’s experience post-franking has shown a continuation of this trend

Myth 7: Abolishing franking would boost government revenue

Reality: Franking creates integrity in the corporate tax base. Removing franking would give rise to behavioural changes that could significantly erode the corporate tax base, leaving government finances – and retirees – worse off

Australia is a first-world nation, with first-world community expectations for the services that its government will provide. As such, we can never compete with smaller or less-developed nations that offer low or even zero company tax rates to attract corporates.

Fortunately, the franking mechanism means that for the majority of companies, the corporate tax take – at whatever level it is set – washes through at the shareholder level. There is a subset of companies – those early stage, capital-consumptive, high-growth businesses that can profitably retain and reinvest every dollar they earn – that do not pay out their franking credits and thus would prefer a lower corporate tax rate. In theory, the risk is that these companies will relocate to a more favourable tax locale. But tax is not the sole variable. We must ensure that other policy settings (R&D tax settings, labour market flexibility, immigration flexibility, low bureaucratic “red tape”, etc.) work together to make the Australian community a great place to start – and grow – a business.

So a lower corporate tax rate could, at the margin, benefit and retain more of these mid-sized growth businesses. However, there is a different and very significant risk that must be taken into account. On a direct peer-group comparison basis, overseas companies exhibit more “lazy cash”. Intuitively, we suspect this is related to their reluctance to repatriate cash earned outside of the US into the US tax system.

However for Australian companies, franking creates a strong incentive for local exporters to retain a large tax liability within Australia, since franking credits are only generated on Australian tax paid. Thus franking limits the scourge of tax minimisation that erodes the corporate tax bases of other first-world nations. This highly beneficial incentive structure should not be given up lightly

Myth 8: Franking disadvantages Australian companies that earn significant overseas revenue

Reality: These companies benefit from the positive side effects of franking; empirical evidence does not suggest a disadvantage

Relative to their direct peers listed on other share markets, Australian companies with significant overseas revenue (“exporters”) show lower debt levels yet higher rates of asset growth:

But they have delivered higher CFROI and enjoy a lower cost of capital:

As a result, they have achieved a higher income return than their international peers – and a higher price return, resulting in a significantly higher total return

They have also outperformed their more domestically-focused Australian peer companies

It is hard to see signs of disadvantage here

Myth 9: Franking creates a risky equity-market bias for retirees

Reality: Franking does create a bias toward high-quality, well-managed, cash-generative equities; this will help keep self-funded retirees off the aged pension

Superannuation funds do show a bias towards domestic equities:

But at the SMSF level, this is directed towards the more stable end of the equity market. Credit Suisse research shows that self-managed super funds own about 16% of the Australian equity market. Credit Suisse discussions with advisers to these funds suggests that these investors want high-dividend yields from large companies they identify with and have a history of dividend growth. They have a Tier-1 group of stocks that includes the big four banks and Telstra. The equity-ownership incentive created by franking does not prompt investment at the speculative end of the market, which lessens the risk of retirees experiencing permanent loss of capital. This exposure to quality, cash-generative growth assets is likely to help retirees maintain their purchasing power throughout an extended retirement, and avoid falling back on the aged pension

Myth 10: Franking creates a risky home-market bias for retirees

Reality: Franking results in well-managed, high-returning, lower-volatility companies that are justifiably attractive to domestic and international investors

Franking constrains the reinvestment behaviour of Australian companies. This results in leaner balance sheets, higher returns and lower volatility of returns. They are acutely aware of the importance of maintaining sound balance sheets and of achieving high returns not just fast growth. On the back of this – and deservedly for other reasons – Australian companies have developed a reputation for being well-managed.

As a result of this, Australian companies are favoured by international institutional investors, not just local retirees. This is evidenced by the cost of capital enjoyed by Australian companies, which is in line with that experienced by US companies

A low cost of capital benefits all Australian enterprises. It promotes entrepreneurship and capital formation

Myth 11: Franking makes Australian shares less attractive to overseas investors

Reality: Corporate tax levels do not typically feature in investment decisions by foreign investors. Quality of operations and management are more significant; franking supports these

Perhaps the only time that tax would come into consideration would be if a new tax, such as the recently proposed mining tax, was imminent or corporate tax levels were to rise to a large extent. Australia’s dividend imputation system is a non-issue for global equity investors.